Another look at sex offender registration laws

North Carolina had a problem. Its sex registration law had just been thrown out by a Federal judge as being vague and overbroad. Hard to quibble with that; among other things, the law prohibited offenders from being "at any place where minors gather for regularly scheduled educational, recreational, or social programs." It had been interpreted to preclude offenders from going to G-rated movies, eating at a McDonald's if it had a play center, or attending church.

So North Carolina doubled down, passing a new law which more specifically states the venues from which sex offenders are barred: places where minors "frequently congregate," like libraries, amusement parks, swimming pools, and, for good measure, fairgrounds during any state fair.

The judge will probably get to look at this again, but before he does, he might want to read the 6th Circuit's recent decision in Doe v. Snyder. It's about as withering a broadside against sex offender registration laws (SORA) that you're likely to see.

If you're a kid and you had a law named after you, you probably came to a bad end, and that's particularly true of SORA statutes. Eleven-year-old Jacob Wetterling disappeared in 1989, and that led to the Jacob Wetterling Act, which required states to set up registries of sex offenders. (His body was just found last week.) Then in 1994, seven-year-old Megan Kanka was raped and murdered by a neighbor, a two-time sex offender. That led to Megan's Law, which provided for community notification of the whereabouts of sex offenders, limited where they could live, required them to register more frequently, and to advice officials of when they moved.

And then we come to the Adam Walsh Act, passed by Congress in 2006, and adopted in Ohio the following year. Michigan adopted it when it first came out, and that's the subject of Doe v. Snyder.

The thing to keep in mind about SORA laws is that they've been applied retroactively. The plaintiffs in Doe had all committed their offenses several years prior to the passage of the AWA, but the law still regulated their conduct. They complained this violated the Constitution's Ex Post Facto Clause, but that hinges on whether the registration requirements are punitive; if something isn't punishment, the Ex Post Facto clause doesn't apply. That hadn't been a problem in the past; in fact, in 2003 the US Supreme Court in Doe v. Smith rejected such a challenge, holding that Alaska's Megan's Law was "remedial," not punitive.

No more. Five years ago, in State v. Williams (discussed here), the Ohio Supreme Court held that the changes in the AWA had made the statute punitive, and that the law couldn't be applied to defendants convicted before its effective date. The dissenters argued, among other things, that "every federal circuit court of appeals to consider whether the Federal Adam Walsh Act is constitutional has held that it may be retroactively applied to sex offenders who committed sex offenses prior to its enactment."

Well, no more with that, either. Snyder makes a more thorough analysis of the application of the Ex Post Facto Clause than does Williams, but it arrives in the same place. The two critical questions in determining whether the law is punitive is whether the legislature intended it to be punitive, and whether its actual effects are. The court accepts the statute's prefatory bullshit about it being intended merely to "provide law enforcement and the people of this state with an appropriate, comprehensive, and effective means to monitor those persons who pose such a potential danger."

But then we get to the actual effects, and the opinion lists five factors that are relevant:

(1) Does the law inflict what has been regarded in our history and traditions as punishment?

(2) Does it impose an affirmative disability or restraint?

(3) Does it promote the traditional aims of punishment?

(4) Does it have a rational connection to a non-punitive purpose?

(5) Is it excessive with respect to this purpose?

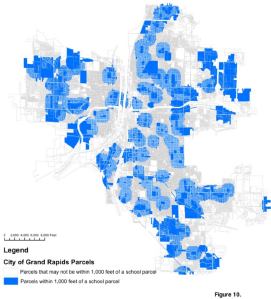

The law flunks the first two. It really fits into the ancient punishment of  banishment, and the opinion gives us a map of Grand Rapids, with the areas prohibited to sex offenders in blue. And the law does impose restraints; the restrictions are far more restrictive than those approved in Smith. On the other hand, while it does promote traditional aims of punishment, there's a regulatory scheme here, so that factor is entitled to little weight.

banishment, and the opinion gives us a map of Grand Rapids, with the areas prohibited to sex offenders in blue. And the law does impose restraints; the restrictions are far more restrictive than those approved in Smith. On the other hand, while it does promote traditional aims of punishment, there's a regulatory scheme here, so that factor is entitled to little weight.

The latter two are intertwined, and here's where the opinion becomes something more than just a general beat-down of sex offender laws. There was little factual record in Williams, due to the fact that the question came up in an ordinary criminal case: the parties submitted briefs, the judge ruled, and up it went.

In Doe, though, the parties had developed an extensive factual record in the lower court. The panel found that that record "provides scant support for the proposition that SORA in fact accomplishes its professed goals." Here's the money quote:

Even more troubling is evidence in the record supporting a finding that offense-based public registration has, at best, no impact on recidivism. In fact, one statistical analysis in the record concluded that laws such as SORA actually increase the risk of recidivism, probably because they exacerbate risk factors for recidivism by making it hard for registrants to get and keep a job, find housing, and reintegrate into their communities ... SORA puts significant restrictions on where registrants can live, work, and "loiter," but the parties point to no evidence in the record that the difficulties the statute imposes on registrants are counterbalanced by any positive effects. Indeed, Michigan has never analyzed recidivism rates despite having the data to do so.

The plaintiffs had raised a number of other issues about the law, arguing that portions violated freedom of speech and association. The panel finds these arguments "far from frivolous" and "of great public importance." Since the ruling on the Ex Post Facto Clause makes them inapplicable to the plaintiffs, though, that moots those other issues.

For now, anyway.

Comments