Thursday Roundup

A different definition of "gun nut." In the wake of District of Columbia v. Heller and McDonald v. Chicago, the recent SCOTUS decisions holding that the 2nd Amendment guarantees an individual right to bear arms, rather than a collective one, a number of commentators, including Your Faithful Correspondent, anticipated a wave of cases striking down gun laws as being overly restrictive, and legal debates as to whether any law infringing on gun rights had to be subjected to "strict scrutiny," the same as, for example, a law impinging on First Amendment rights. That didn't happen.

Until maybe now. Three weeks ago, in Tyler v. Hillsdale County Sheriff's Department, the 6th Circuit struck down a Federal law which prohibited 73-year-old Clifford Tyler from possessing a gun because he'd involuntarily spent a short time in a mental institution thirty years ago. The court did apply the strict scrutiny test, even though one of the judges acknowledged that the law would've flunked the less demanding heightened scrutiny test.

This is the first time a Federal court has applied strict scrutiny, or struck down a Federal gun statute post-Heller, and it raises some interesting questions, not only about Federal gun laws but state ones as well. Giving a friend a joint is a fourth degree misdemeanor in Ohio, but conviction of that will disable you from possessing a gun for the rest of your life, and doing so is a third degree felony. Would that survive strict scrutiny?

You think we've got a corruption scandal. Back in December, as detailed here, County Prosecutor Tim McGinty launched an investigation on judicial corruption among the common pleas judges -- or, more accurately, an investigation to determine whether there should be an investigation. The focus of McGinty's ire was his longstanding belief that judges assign criminal lawyers for indigent defendants based upon the lawyers' contributions to the judges' campaigns.

McGinty presented the court with a five-page record request seeking virtually every scrap of paper, in real or digital form, pertaining to the assignments over the past several years. The scope of the request elicited concern from Administrative Judge John Russo, but a constitutional crisis was averted when Chief Justice Maureen O'Connor interceded and "persuaded" the two to punt the issue to the Commission on the rules of Superintendence for the Supreme Court. Hearings will be held, testimony will be taken, reports will be made, and the net result will likely reinforce the French philosopher's observation that a committee is an alleyway down which ideas are lured to be strangled.

But just as I was beginning to feel guilty about ponying up a Franklin to eat cold food at a judge's fundraiser to get an assignment where I'd get paid $50 or $60 an hour, I came across this article from Newsday. (H/t to Overlawyered.) There are all kinds of appointments judges in Nassau County, New York, can make: receivers, temporary property managers, and the like. One attorney, Steven Schlesinger, pocketed $628,000 in fees from judicial appointments since 2010. Coincidentally, he happens to be one of the party leaders who name judicial candidates.

That's not confined to New York. Back in 2009, the Plain Dealer did an investigation which revealed that Domestic Relations Judge James Celebrezze appointed his friend, Mark Dottore, to serve as the receiver and handle assets in eleven hotly-contested divorce cases in the last six months of 2008. Celebrezze didn't appoint anyone else to serve in that capacity. Dottore and his company received $225 an hour, which worked out to $340,000 over that six-month period. I said "company," not "firm": Dottore isn't a lawyer. He did serve as the campaign treasurer, and threw a fundraiser, for Leslie Ann Celebrezze, Celebrezze's daughter and the successor to his seat.

And then, of course, there's the common pleas court's commercial docket. That was a pilot program initiated in 2009, where all commercial cases -- business disputes -- would be assigned to one of two judges. The idea was that the judges would gain expertise in that area, and businesses would therefore be more likely to locate to Cleveland.

The idea wasn't specific to Cuyahoga County. A number of other counties had commercial dockets. (The Supreme Court has since modified the Rules of Superintendence to allow for this.) Franklin County judges voted to eliminate their commercial docket because, according to one judge, "it became a political football because business litigation often attracts premier attorneys who can be generous donors to judges when they're running for election." There was talk about scuttling it up here, but instead the docket was expanded to four judges instead of two, with a three-year "term." The discerning reader will note that if the purpose of having a commercial docket is to allow the judges on it to gain expertise in the area, it makes little sense to limit their terms to three years. That point was noted by a local law professor, who opined that the limit was "perhaps a political compromise." Ya think?

Willie Sutton said he robbed banks because that's where the money was. It takes money to run for judge; even if you're unopposed, you have to shell out $7,500 to the party just for the campaign leaflet it puts out. I don't think any judge is figuring to get over the hump on the contributions of criminal defense attorneys.

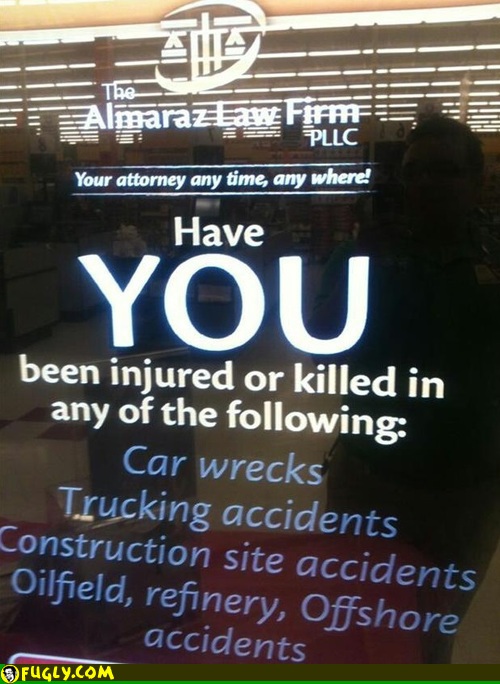

Coming soon to Ohio. Let's welcome the Almaraz Law Firm.

Google says they're from Texas, but the ad does say "anywhere." If you've been killed, I think it's probably more urgent that you make an appointment than if you've merely been injured.

Comments