What's Up in the 8th

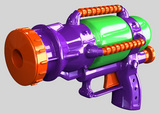

I once had a case where my client was charged with four

counts of aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon, each carrying one- and

three-year firearm specifications. At

the first pretrial, I pointed out to the prosecutor that the "firearm" was a

toy gun, which had proved utterly useless as a weapon; the defendant's intended

victims had taken it away from him and beaten him with it. "Well, I guess they missed that in the grand

jury, huh?" he responded.

But the six pages of exposition serve only as a launching point

for the metaphysical inquiry, when is a toy gun a deadly weapon? Over the next dozen pages, the court

exhaustively analyzes the case law, and the answer appears to be: when it can be used as a bludgeon. That's not the case here; the panel informs

us that "our own examination of the toy gun shows it is made of light plastic,

weighs 1.5 ounces and measures 5 inches in length and 3.5 inches in height;

clearly not a device that was proven in any manner capable of inflicting death." The conviction is modified to one of simple

robbery by force, a second degree felony, and the case is remanded for

sentencing.

The court tackles another issue that has long been the

subject of philosophical debate in State

v. Kent. Kent meets 15-year-old

on the Internet, chats her up, arranges a meeting, treats her to dinner at

McDonald's, then takes her to a laundry room in his apartment building and

announces, "We about to fuck." The girl manages to resist Kent's

charms, announces, "No, we not," and leaves. Does this

constitute importuning, i.e., soliciting a minor for sex, which is in turn

defined as "to seek, ask, invite, tempt, lead on, or bring pressure to

bear"? Kent argues on appeal from his

conviction that he was just "discussing" sex, but the court finds

that "although Kent's statement was not an eloquent request to have sex

with T.C., it clearly was intended for that purpose." Yes, we can

definitely rule out "eloquent."

The big case, though, is In

re C.T., which features the modern version of the boy-meets-girl story,

the one which culminates with her performing oral sex on him in her car after a

football game while he penetrates her vagina with his finger. In his trial for rape in juvenile court, the

prosecutor was allowed to cross-examine C.T. on a his plea to a previous charge

of gross sexual imposition, in which he was accused of forcing a girl to

perform oral sex on him while he digitally penetrated her. The 8th District reversed on the basis of its

decision in State v. Williams, finding

that this wasn't proper 404(B) "other acts" evidence. But the State appealed both Williams and C.T., and the Supreme Court reversed Williams (discussed here) and

remanded C.T. for reconsideration in

light of Williams.

Williams had

employed a three-step analysis to determine admissibility of 404(B) evidence: (1) whether the evidence is relevant, (2)

whether it's used to prove the defendant's character and that he acted in conformity

with it (a no-no), or whether it was admitted for a proper 404(B) purpose, and

(3) whether the probative value outweighed the prejudicial effect. The court in C.T. applies that test and comes to the same conclusion it did

before. The evidence isn't relevant

because, unlike Williams, C.T.'s

conduct didn't show a "unique behavioral fingerprint." Williams

had involved evidence that the defendant, a teacher, targeted young boys

who lacked a father figure, then groomed them for sexual activity. The State's argument in C.T., besides the similarity in the sex acts, was that "in both

cases he found an opportunity to be alone with a young female"; as the court

aptly notes, "[f]inding an opportunity to be alone with another is a necessary

part of engaging in sexual conduct, whether lawfully or not." [Slaps forehead; so that's what I was doing wrong...]

The purpose of the evidence, the court decides, was to show conformity -

"to prove that C.T. had a propensity to engage in sexual conduct with a female

without consent" - rather than one of the purposes allowed by 404(B), and the

evidence was obviously prejudicial, since the judge had specifically cited it

in his adjudication of delinquency.

It's been my observation that appellate and supreme courts tend

to come up with "steps" and "factors" to be applied, without giving much

thought to whether it really makes sense, and the C.T. court's application of the three-step analysis in Williams reveals the logical

deficiencies in the latter. As I pointed

out when Williams came down, the

first step is meaningless: whether it's relevant

is the first step in determining the admission of any piece of evidence. The distinction between that and the "purpose"

of the evidence - whether it's intended to prove character or to prove a proper

404(B) purpose - is difficult to discern, as evidenced by the opinion in C.T.:

that whole discussion is contained in the opinion's analysis of the

first step. As for prejudice, I'll go

with what I've said before: I have yet

to see a case where an appellate court found that the evidence was admissible

under 404(B), but shouldn't have been admitted because it was too prejudicial.

In reality, C.T. was

largely determined by the facts: the

girl had played a major role in instigating the event, and had testified at trial

that if C.T. had agreed to be her boyfriend after the incident, they wouldn't

be in court. Had the defendant in Kent had a prior incident in which he'd

lured some girl to his apartment building to have sex with her, I have little

doubt that the court would have deemed it proper 404(B) evidence. The court came to the correct result in C.T., and is to be congratulated, I

suppose, for its rigorous application of the Williams three-step analysis. But sometimes, all an analysis does is dress

up a court's gut reaction to what should be the law. And that's not a bad thing.

Comments