What's Up in the 8th

As I've mentioned before, appellate law isn't for those who have self-esteem issues; the state's winning  percentage in criminal appeals usually runs between 80 and 90 percent. When I sit down each week to do my post summarizing the 8th's decisions, I usually have my old friend Jimmy Beam on hand as I brace myself for the cavalcade of opinions batting away defendant's arguments as "devoid of merit," followed by a breezy "judgment affirmed." The past month, for example, has seen only about three reversals, other than in sex offender classification cases.

percentage in criminal appeals usually runs between 80 and 90 percent. When I sit down each week to do my post summarizing the 8th's decisions, I usually have my old friend Jimmy Beam on hand as I brace myself for the cavalcade of opinions batting away defendant's arguments as "devoid of merit," followed by a breezy "judgment affirmed." The past month, for example, has seen only about three reversals, other than in sex offender classification cases.

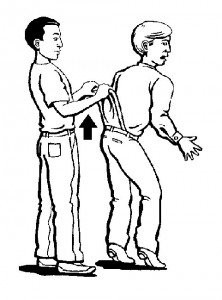

So imagine my surprise when I went through the dozen criminal cases the 8th churned out last Thursday, and found no fewer than eight reversals, including a high profile aggravated murder case which we'll discuss tomorrow, as County Prosecutor Bill Mason suffered his worst week since getting an atomic wedgie back in 9th grade gym class. (Artist's rendition at right.)

Some of them came as no surprise. Three years ago, in State v. Chambliss, the 8th considered a case in which the trial judge had peremptorily removed the defense lawyers, for no apparent reason. In line with Ohio Supreme Court precedent, the court found there was no final appealable order, but this April the Supreme court overruled that precedent and returned the case to the 8th. As expected, the 8th reverses, the state taking no position on the matter.

State v. Bronston is another reversal which could have been anticipated. Bronston had been convicted of a sex offense in 2004, and was brought back before the court in 2010 for proper imposition of post-release controls. The judge did that, but also raised Bronston's sex offender classification to Tier III, in accordance with the Adam Walsh Act. This contradicted the Supreme Court's decision in State v. Fischer that in resentencing because of a post-release controls error, only PRC can be addressed, and 8th District precedent that a judge is not authorized to address a defendant's previously-imposed sex offender classification in resentencing to impose PRC.

An easy reversal is also found in State v. Holloway. Holloway was charged with kidnapping (convictions for intimidation of a crime victim and domestic violence were affirmed), with the victim denying at trial that her liberty had been restrained. This was contrary to her statement to the police, and so the judge allowed the prosecutor to have her read it into the record, and then admitted it into evidence as well. There are ways to use a prior statement in this fashion, but none were properly employed; no attempt was made to show surprise or affirmative damage, which would allow the State to impeach its witness, and the impeachment was improper anyway (the prosecutor had the victim read the statement, before laying any foundation for admission of the inconsistent statement), there was no basis for using it to refresh her recollection, since she didn't indicate she couldn't recall any of the events, and even if any of these had been done, there's no basis for allowing the statement to be introduced as substantive evidence.

But then things get more complicated. In State v. Daley, the judge finds the defendant incompetent to stand trial based on psychiatrist's opinion that he was a "radical Christian" who "expresses such extreme intensity of religious belief in very unorthodox religious beliefs to the point to constitute psychosis." Typical of Daley's "unorthodox religious beliefs" is his description of divorce court as "the high court of Satan," an observation which would probably find murmured concurrence among half the practitioners there. The ACLU filed an amicus brief on Daley's behalf, arguing that his religious beliefs were protected by the First Amendment, and the court agrees that since "the diagnosis was based solely on Daley's religious beliefs. . . the trial court court erred in finding him incompetent."

Two problems here. The cases cited by the court deal with situations in which people were penalized for their religious beliefs (prosecuted for handing out religious pamphlets) or the state tried to take action to override their religious principles (force a believer in faith healing to seek medical treatment for a tumor). That last case might seem to apply to Daley, since the finding of incompetency was coupled with an order for forced medication. But the court doesn't address the latter, only the former. Even more worrisome is the notion that any religious belief, no matter how delusional, insulates one from being found incompetent. If my client decides I'm one of the devil's henchmen and refuses to help me with his defense, does that mean he has to stand trial?

State v. Wright stands on firmer footing. The case involves a sordid tale of Wright, then aged 30, beginning a dalliance with a 12-year-old girl, which continued until just before her sixteenth birthday; she became pregnant, and DNA evidence confirmed Wright as the father. He was convicted of one count of rape and several of unlawful sexual conduct with a minor.

One problem. That part about Wright being 30? There was no evidence ever introduced of Wright's age. That becomes key, because sexual conduct with a minor is normally a fourth degree felony, but becomes a third degree if the defendant is ten or more years older than the victim. The court correctly finds the evidence insufficient to support the ten-year specification, but instead of simply reducing them to 4th degree felonies, vacates the convictions entirely. The State's rape case fares only slightly better; it gets reversed, because of the evidence introduced of Wright's sexual episodes with the girl after she moved out of state (and hence not part of the charges in this case), and the DNA results. The State argues that the evidence is admissible to show a "common scheme" because the events are "inextricably related" to the charges, and that the DNA evidence proves Wright's identity as the perpetrator. Not so, correctly counters the court: the out-of-state acts occurred months to years after the charges here, and the charges could have been proved without reference to them, so they're not inextricably linked. And the 8th continues its excellent work on 404(B) evidence, noting that the proof of identity exception isn't applicable where identity is not disputed, as was the case here: the dispute was over whether Wright did it, not over who did.

The State does wind up one for two in cases involving a defendant named Wright, and the other State v. Wright provides a procedural primer. Wright pled guilty to weapons under disability and child endangerment, then appealed his four-year sentence. He also filed a motion with the trial court to withdraw his plea, which was denied. On appeal, he also argues that the trial court erred in denying the motion, but there's a problem: he didn't file an appeal from that order, nor did he ask to amend the appeal to include it, so the court won't address it. As for the appeal of the sentence? Well, he didn't file a transcript of the sentencing, either, so that goes down the tubes, too.

The court's reversal binge carries over into civil cases, but the plaintiff's victory in Beegle v. South Pointe Hospital will prove a Phyrric one. Beegle's malpractice case was dismissed with prejudice for failure to file the affidavit of merit, but the court partially reverses. Beegle's request for extension to file the affidavit was denied, and so the court reviews that for abuse of discretion. That's usually the death knell for claims of error, and it is here, the court frankly acknowledging that "we would likely" have granted the extension, but that the trial judge's ruling wasn't sufficiently unreasonable to warrant reversal under the more deferential standard. The court does partially reverse, finding that the dismissal should have been without prejudice, but that does Beegle no good. Just last week in Graf v. Cirino, the court held that you can't use the savings statute more than once to refile a case. Beegle presents exactly the same situation -- he'd earlier voluntarily dismissed his claim, and used the savings statute to refile it, then been kicked out again for failure to file the affidavit, then refiled -- and so it will fall upon Beegle's lawyer to relate the good news/bad news joke.

Comments