Hard time

There's a perception among a sizable portion of the public that prisoners are "coddled": that a prison sentence guarantees you not only three hots and a cot, but color TV, computers, conjugal visits, and all the amenities of home, except that somebody tells you when you have to eat, but hell, your wife does that anyway, right?

Reading the Supreme Court's decision last week in Brown v. Plata might disabuse people of that notion.

California's prison systems have been operating at 200% of capacity for over a decade. What that does for  normal prisoners is bad enough: 200 living in a gymnasium, as many as 54 sharing a single toilet. (That presents some safety problems for the guards, too: those 200 prisoners in the gym are supervised by as few as 2 or 3 guards.) But what overcrowding does in terms of treatment for mentally or physically ill prisoners is simply appalling. Suicidal inmates ar

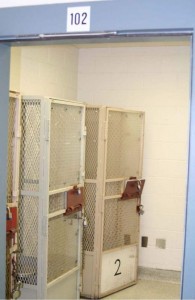

normal prisoners is bad enough: 200 living in a gymnasium, as many as 54 sharing a single toilet. (That presents some safety problems for the guards, too: those 200 prisoners in the gym are supervised by as few as 2 or 3 guards.) But what overcrowding does in terms of treatment for mentally or physically ill prisoners is simply appalling. Suicidal inmates ar e held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets, like those on the left; one psychiatrist reported seeing an inmate who'd been held in one of those cages for 24 hours, standing in a pool of his own urine, nearly catatonic. As a result, the suicide rate at California's prisons are about 80% higher than the national average for prison populations.

e held for prolonged periods in telephone-booth sized cages without toilets, like those on the left; one psychiatrist reported seeing an inmate who'd been held in one of those cages for 24 hours, standing in a pool of his own urine, nearly catatonic. As a result, the suicide rate at California's prisons are about 80% higher than the national average for prison populations.

Physically ill inmates fare no better; because of a lack of treatment space, as many as 50 sick inmates can be held together in a 12-by-20 foot cage for up to five hours. Death is a frequent result of the delay in diagnosis: a 16 month delay in evaluating an abnormal liver mass; an 8 month delay in receiving regular chemotherapy; a 17 month delay in diagnosis of jaundice. One inmate with severe abdominal pain died after weeks without seeing a specialist; another with "constant and extreme" chest pain died after evaluation by a doctor was delayed for eight hours. One inmate died of testicular cancer; no work up for cancer was done during the 17 months he complained of testicular pain.

This is not a recent development. The first lawsuit complaining of these conditions was filed 21 years ago. Nor is California unique; while its problems are more extreme, most states have experienced overcrowding as a result of the "lock 'em up and throw away the key" mentality which has driven criminal justice policy for most of the past forty years, and has resulted in America having the largest prison population in the world. That's not per capita; we lock up more people in this country than China does with a population more than four times larger than ours.

The question is what to do about it. There's an 8th Amendment issue here; as Kennedy, writing for the 5-member majority in Plata, put it, overcrowding

creates a certain and unacceptable risk of continuing violations of the rights of sick and mentally ill prisoners, with the result that many more will die or needlessly suffer. The Constitution does not permit this wrong.

That has been the basis for Federal court involvement in state prison management, which, in some cases, dates as far back as the 1970's. In the late 1980's, for example, a Federal judge in Pennsylvania imposed a stict population cap on Philadelphia's jails, forcing them to release several hundred inmates a week.

Then one of them went out and murdered a rookie police officer, and that prompted Congress to pass the 1995 Prison Litigation Reform Act. The Act greatly limited the authority of Federal judges to order the release of inmates: such orders had to be "truly necessary" to avoid violation of the inmates rights, had to be issued only as a last resort, and requires that state officials be given time to pursue alternatives to release.

Plata was the first case on the PLRA to reach the high court, and the questions boiled down to those framed by the Act: was the release of 36,000 inmates over the next two years, as proposed by the three-judge District Court panel overseeing the prisons, and and affirmed by the 9th Circuit, the only way of solving the problem? The battle lines were clearly, and predictably, drawn at oral argument last November. The four liberals -- or what passes for liberals on today's Court -- pummeled the State's attorney with questions as to how much more time would California need to rectify the problem. The attorney would not even commit to a five-year time frame. The conservatives, on the other hand, raised the safety issue. When the inmates' attorney tried to reassure the justices that the recidivism rate for those released would probably run closer to 17% than the customary 70%, Alito was not comforted; doing some quick calculations, he concluded that that meant that 3,000 were going to commit new crimes.

It was clear that the decision was going to come down to Kennedy, who spent the oral argument indicating that he felt the inmates' case had been clearly proven, but that he was concerned with the remedy. Whatever doubts he had as to the latter issue were dispelled by the time he wrote his opinion. After spending the bulk of thirty pages describing the deplorable conditions found by the District Court, he concluded that "the order's limited scope is necessary to remedy a constitutional violation." The conservative bloc was vehement in its dissent, with Scalia taking the unusual step of reading his from the bench, decrying "the inevitable murders, robberies, and rapes to be committed by the released inmates." Alito ended his with the prediction that the decision "will lead to a grim roster of victims."

As I mentioned, while California might lead in overcrowding, it's not the only contestant in that race. Last year, Ohio's prison population topped 51,000; the state's penitentiaries were designed to hold 38,665 inmates. And we're in good shape; in Alabama, the prisons are operating at 190% of capacity.

Economics has driven a lot of the recent effort by states to cut down on prison overcrowding. Just about every single state faces a budget crunch to some degree, and prisons are where the money is: in most states, only Medicaid costs have risen faster. After last week, Plata may have given some added impetus to that effort.

Comments