Other acts

There are few things more vexing for defense attorneys, especially in child sex cases, than "other acts" testimony under EvidR 404(B). You have a hard enough time explaining to the jury why some 12-year-0ld is claiming that your client made her do nasty things, and then the prosecutor puts on another 12-year-old to say that your client did nasty things to her, too.

Stephen Ogletree found himself in that situation. Ogletree owned a house where a mother and her twelve-year-old daughter lived. The daughter claimed that Ogletree began helping her with her homework, but that his "help" soon devolved first into fondling, then rape. At trial, the state produced another witness, also a previous tenant of Ogletree's, who claimed that when she was 16, Ogletree asked her to come inside to help fix a light bulb, and when she did, touched her buttocks and vagina. Despite the fact that Ogletree had been charged in that incident and acquitted, the judge let it in.

Last week, in State v. Ogletree, the 8th District decided that was the wrong decision.

The court's opinion on that point initially doesn't augur well for Ogletree, the court deciding to use the abuse of discretion standard in reviewing the matter. (A couple weeks ago, I discussed a 9th District decision that made a compelling case that de novo review is in fact the correct standard.) But things get better in a hurry.

The general rule is that evidence of prior crimes of the defendant is barred, but the rule establishes various exceptions to that. Perhaps the most troublesome is the "common scheme, plan, or system. (Which actually isn't found in the rule; it's found in the "other acts" statute, RC 2945.59.) The State figured the evidence here clearly fell within that exception: Ogletree was charged with fondling a young girl who was a tenant of his, he had fondled another young girl who was a tenant of his, end of story.

But that's not the way it works. As the court explains, "scheme, plan or system" evidence is relevant in two situations. The first is where the other acts are inextricably related to the crime at issue; basically, they form an immediate background to the offense. That obviously wasn't the situation here; although the opinion doesn't say when Ogletree was supposed to have committed the other offense, from the docket it appears that his trial on that was two years earlier.

The second situation was explained by the Supreme Court back in 1975:

Identity of the perpetrator of a crime is the second factual situation in which 'scheme, plan or system' evidence is admissible. One recognized method of establishing that the accused committed the offense set forth in the indictment is to show that he has committed similar crimes within a period of time reasonably near to the offense on trial, and that a similar scheme, plan or system was utilized to commit both the offense at issue and the other crimes.

This is sometimes referred to as the "behavioral fingerprint" exception, and it makes sense. If the defendant is charged with committing a crime in a distinctive manner, proof that he has committed other crimes in that particular manner is relevant to showing that he's the person who committed the crime charged.

But, as the court explains, that's when identity is at issue. Here, there was no question of identity: the issue was not who fondled and raped the victim, but whether that happened at all.

This is an important distinction to make. Too often, prosecutors, judges, and even defense attorneys think of the "scheme or plan" exception as being an end in itself: if the defendant did something very similar to what he's charged with, that can be introduced to show that he did it again. As Ogletree makes clear, that's not the way it works: the scheme or plan must go to one of the other exceptions in the rule.

In fact, the concurring opinion does perhaps an even better job of highlighting the problem with the state's approach:

The state’s argument in support of admitting the other acts testimony was based on nothing more than the allegation that Ogletree had twice assaulted young women who lived in his rental property. This improperly conflated opportunity with scheme or plan. As the majority opinion notes, Ogletree’s opportunity to be present on the premises was obvious because he was the landlord, did repairs in the home, and still had his mail delivered to the premises. Barring any other similarity in how the separate alleged instances of sexual assault occurred, there was no basis for the court to find that Ogletree acted according to some scheme or plan.

The concurrence also finds fault with the trial judge's curative instruction, which told the jury that the "evidence was received only for a limited purpose," and that it could not consider the evidence "to prove the character of the Defendant in order to show that he acted in conformity with or in accordance with that character.” The concurring judge notes, "This instruction begs the questions: How should the evidence be considered? What was the 'limited purpose' for which it was received?"

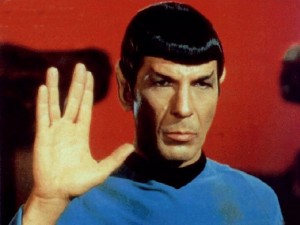

This in turn begs the question of what possible curative instruction could be given that would make sense to twelve people who didn't eat law for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Curative instructions generally come in two flavors: Ignore This, and Use This Evidence in a Certain Way. The curative instruction regarding the defendant's prior convictions is an example of the latter: you can consider the fact that the defendant was convicted of robbing people on three previo us occasions in determining whether he's telling the truth that he didn't rob the people on this occasion, but you can't use it to determine whether he robbed the people on this occasion. That's hard enough for anyone to understand, but the instruction on how to use other acts evidence -- basically, that you can't use it to determine whether the defendant is the kind of guy who would do this sort of thing, but you can use it to determine whether he did it -- requires logical contortions that would test the guy on the right.

us occasions in determining whether he's telling the truth that he didn't rob the people on this occasion, but you can't use it to determine whether he robbed the people on this occasion. That's hard enough for anyone to understand, but the instruction on how to use other acts evidence -- basically, that you can't use it to determine whether the defendant is the kind of guy who would do this sort of thing, but you can use it to determine whether he did it -- requires logical contortions that would test the guy on the right.

The 8th District has done a fairly good job over the past few years with 404(B) cases, making distinctions that other courts have failed to make. Typical was the decision last year in State v. Greer, where the state attempted to introduce evidence of defendant's previous convictions for drunk driving in an effort to show "absence of mistake" in his driving on the sidewalk while allegedly under the influence of drugs. As the court correctly noted, "Appellant did not claim that he accidently or mistakenly drove under the influence of alcohol or drugs. His defense was that he was not under the influence at all.” The state's attempt to introduce evidence of Ogletree's alleged sexual advance on another tenant was simply an effort to show that Ogletree was the kind of guy who did that sort of thing. Use of evidence in this fashion is exactly what 404(B) bars, and kudos to the court for recognizing it.

Comments