What's up in the 8th

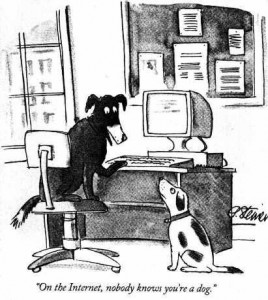

I've often wondered if there's a "law enforcement" chatro om on AOL, where everybody on it is actually a teen-age girl pretending to be an FBI agent. Two defendants in 8th District cases last week forgot the important lesson conveyed by the cartoon on the right, to their sorrow. Other cases show the limits of Arizona v. Gant, and the expansive nature of "consensual encounters." That, plus a good decision on expungement, fill out the 8th's body of work over the past couple of weeks.

om on AOL, where everybody on it is actually a teen-age girl pretending to be an FBI agent. Two defendants in 8th District cases last week forgot the important lesson conveyed by the cartoon on the right, to their sorrow. Other cases show the limits of Arizona v. Gant, and the expansive nature of "consensual encounters." That, plus a good decision on expungement, fill out the 8th's body of work over the past couple of weeks.

I don't know if any criminal defendants, real or potential, read my blog, but it probably wouldn't be a bad idea. Then maybe they wouldn't do dumb things like say, "Sure, officer, you can search my car." In truth, though, someone who's dumb enough to say that he wouldn't have consented to a search if he'd remembered that he had cocaine in his pocket is probably beyond my help, or anybody else's. In any event, that scenario is played out in three separate cases.

In State v. White, the cop observes the defendant apparently sleeping in a parked car, and approaches the vehicle. After White says he's all right, the officer asks for identification, finds that White's license is suspended, arrests him, and asks if he's got any weapons in the car, to which White helpfully responds that the're a gun in the console. State v. Jones and State v. Smith involve similar situations. In the former, an officer sees a vehicle with its rear door open to traffic and the defendant with his legs sticking out of the car; upon stopping to investigate, Smith gets out and promptly drops a rock of crack cocaine, then tells the officer there's more stuff inside; the officer searches and finds two more bags. In the latter, the police get a tip about some guys in a parking lot using drugs in a car. They go to the lot, see the defendant in the car, and ask him about the drugs. He denies it, so they ask for consent to search the car, which he gives them, resulting in the discovery of a gun, resulting in his arrest, resulting in the discovery of drugs in his pocket when he's booked.

The theme of all three cases is that the police don't need probable cause, reasonable suspicion, or anything else to approach you and ask if they can search you or your car. (Unless, of course, they approachwith guns drawn, or in sufficient numbers that consent is merely submission to authority.) Jones also shows that the hoopla over Arizona v. Gant (discussed here) isn't entirely warranted. Despite the fact that Jones had been arrested and handcuffed before the search of his car took place, Gant isn't mentioned. The prosecutor's office apparently thought it would be, because they argued in both courts that the evidence would have been inevitably discovered when the car was inventoried. No need for that argument; the discovery of the crack dropped by the defendant gave probable cause to search the car, and search incident to arrest was no longer implicated.

State v. Hendricks also involves a search issue. Hendricks was on probation for sexually importuning what he thought was a 14-year-old girl, who turned out, to no one's surprise except his own, to be a police detective. Hendricks' probation officer got a tip that he had child pornography on his computer, so went to his home with several Sheriff's deputies and made a search of his computer, and confirmed the tip. The court notes that Hendricks consented to searches as a condition of probation, and the opinion contains an excellent summary of the law regarding such searches. In a nutshell, only a reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, not probable cause, is necessary in those cases.

The defendant in State v. Phillips may have tried to hit on the same detective as Hendricks did, but suffered far more dire consequences: despite being only 21 and with no prior record, and an array of family and friends to show support at the sentencing, Phillips got 24 years in prison on two counts of importuning and thirty of pandering sexually oriented material. The odd thing about the appeal is that he argues that the court couldn't impose consecutive sentences without making findings under RC 2929.14(E)(4), and cites in sole support of that a 2003 4th District case. The court finds reliance on the case "disturbing" in light of the later decision in State v. Foster. Yeah, there's that, and how about the even later decision in Oregon v. Ice, which the appeal doesn't mention? Basically, the moral of Phillips' story is that if you're shooting for a lesser sentence (Phillips' attorney argued for probation), you're much better off if the record doesn't show you sending pictures of your genitalia to someone you think is a 12-year-old girl, and telling her it would be "hotter" if she was under 12.

I'd mentioned a couple weeks back about the tough road someone has to go to get a conviction expunged, but State v. M.D. makes that road a little easier. The defendant had filed an application to expunge his ten-year-old convictions for receiving stolen property, forgery, uttering, and obstructing justice. There was no dispute that he was a first offender who hadn't been in any trouble since, but the State still objected on grounds that "this was an extremely important case in our office" and that it opposed expungement because "of the nature of the crime." After a hearing, the trial court denied the application without explanation.

The 8th reverses, holding that while the grant of expungement is within the trial judge's discretion, an appellate court can't determine whether the judge appropriately exercised discretion if the judge doesn't give any explanation for what he did. The court also notes that the nature of offense cannot provide the sole basis for denial, and reverses and remands with instructions that the judge consider the remedial purpose of the expungement statutes, and that they should be liberally construed.

Hint, hint.

Comments