The War on Bong Hits

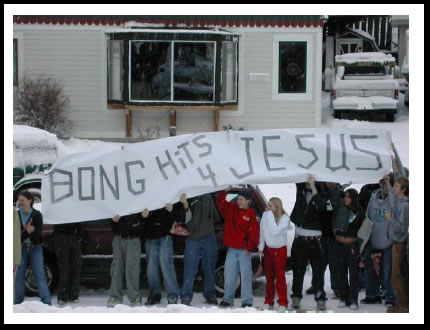

The safety and welfare of the Republic was further ensured last week by the Supreme Court's decision in the famous "Bong Hits" case, Morse v. Frederick, in which a group of students had unfurled a banner, as shown at left, during a school outing to watch the Olympic Torch relay. The outraged principal had immediately demanded that it be taken down, and all but one student had complied. He wound up being suspended for ten days.

The safety and welfare of the Republic was further ensured last week by the Supreme Court's decision in the famous "Bong Hits" case, Morse v. Frederick, in which a group of students had unfurled a banner, as shown at left, during a school outing to watch the Olympic Torch relay. The outraged principal had immediately demanded that it be taken down, and all but one student had complied. He wound up being suspended for ten days.

As students are wont to do these days, he filed a suit for violation of his civil rights. The district court dismissed it on summary judgment, but the 9th Circuit reversed, holding that the school had failed to show that the banner was sufficiently "disruptive" of school activities so as to warrant disciplinary action.

The Supreme Court this term has issued opinions in 19 cases arising from the 9th Circuit. It has reversed in 17 of them. This wasn't one of the lucky two.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote the opinion for the 5-4 majority -- joined, as you might guess, Scalia, Thomas, Kennedy, and Alito -- upholding the school's actions. Breyer wrote an opinion concurring in the judgment, but on the grounds that the Court didn't need to reach the 1st Amendment issue, and dissented from the opinion on that basis. Ginsberg, Stephens, and Souter of course dissented. Thomas concurred in an opinion expressing his belief that the 1st Amendment didn't apply to students at all.

This all started, of course, with Tinker v. Des Moines, the 1968 case in which the Court had upheld students' rights to wear black armbands as an expression of opposition to the Vietnam War, finding that student expression couldn't be suppressed unless it would "materially and substantially disrupt the work and discipline of the school." That was the high-water mark of student freedom, though; the Court backed off that test the next time it confronted the issue, 18 years later, in Bethel School District v. Fraser.

Fraser involved a student's speech to an assembly, in which the student employed what the Court called an "elaborate, graphic, and explicit sexual metaphor." (Similar to what can be found on any episode of Friends during its last few seasons.) The Court had little trouble upholding the school's suspension of the student, although, as Roberts confesses in the Bong Hits case, "the mode of analysis employed in Fraser is not entirely clear." Clear enough, apparently, for the majority in Morse to distill two basic holdings from Fraser: first, that "the constitutional rights of students in public school arenot automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings," something that not even Tinker had disputed, and second that Tinker's "substantial disruption" requirement was DOA.

What's particularly interesting about Morse is the Court's handling of the drug issue. After rejecting the dissent's claim that the banner was mere "gibberish," the majority concludes that it was actually advocating drug use. Roberts' explanation for this conclusion borders on the hilarious:

At least two interpretations of the words on the banner demonstrate that the sign advocated the use of illegal drugs. First, the phrase could beinterpreted as an imperative: "[Take] bong hits . . ."--a message equivalent, as Morse explained in her declaration, to "smoke marijuana" or "use an illegal drug." Alternatively, the phrase could be viewed as celebrating druguse--"bong hits [are a good thing]," or "[we take] bonghits"--and we discern no meaningful distinction between celebrating illegal drug use in the midst of fellow students and outright advocacy or promotion.

The opinion then veers off into a discussion of why "deterring drug use by schoolchildren is an 'important -- indeed, perhaps compelling' interest," in terms vaguely reminiscent of the 1950's "demon weed" drug-ed movies.

Somewhat puzzling is the majority's conclusion that "this is plainly not a case about political debate over the criminalization of drug use or possession," but about restricting speech that "is reasonably viewed as promoting illegal drug use." I say "puzzling" because I don't sense that the majority would have come to a different conclusion if the kids had held up a sign saying "Legalize Drugs."

Perhaps Justice Alito would, because his concurrence, in which Kennedy joined, starts this way:

I join the opinion of the Court on the understanding that (a) it goes no further than to hold that a public school may restrict speech that a reasonable observer would interpret as advocating illegal drug use and (b) it provides no support for any restriction of speech that can plausibly be interpreted as commenting on any political or social issue, including speech on issues such as "the wisdom of the war on drugs or of legalizing marijuana for medicinal use."

Superficially, that's a narrower base than the majority's opinion adopts, and thus Alito's views are controlling. But the same inconsistency exists: doesn't advocating drug usage implicity carry a message about "the wisdom of the war on drugs"? What's the distinction?

This might be one of those cases that's hailed in conservative circles, only to come back to haunt them later. Earlier this week, as this story tells us, a student was disciplined for wearing a t-shirt that said "homosexuality is shameful." Could the school ban this on the grounds that a "reasonable observer would interpret it" as advocating hostilitity toward homosexuals, or is it permissible on the grounds that it can be "plausibly interpreted" as commenting on the wisdom of homosexuality and its behaviors?

Stay tuned.

Comments