Friday Roundup

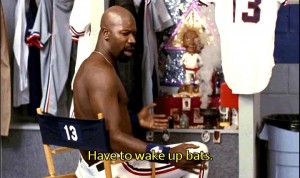

Sticking it to Allstate. What's up with car insurance companies? It used to be that businesses chose a particular spokesman, and stuck with him (or her) until they decided to get a new one. Progressive, for example, is doing nicely with Flo, the bubbly but incredibly annoying clerk at the big Progressive store that looks like a computer software store, except that all of those went out of business yea rs ago. But GEICO finds a need to have no fewer than three: the gekko, the eyes on the stack of money, and the Rod Serling wannabe. Allstate also had limited itself to one, Dennis Haysbert, whose cred as a spokesman was substantially heightened by his stint as president on 24. (Let's put it this way: Allstate certainly didn't hire him based on his role, shown here, as crazed Latino slugger Pedro Cerrano ("bats are frightened") in Major League.) But now they've added another, too: actor Dean Winters, who plays bad cop to Haysbert's good cop (good pitchman/bad pitchman?) by explaining all the mayhem that can be avoided if you have an Allstate policy.

rs ago. But GEICO finds a need to have no fewer than three: the gekko, the eyes on the stack of money, and the Rod Serling wannabe. Allstate also had limited itself to one, Dennis Haysbert, whose cred as a spokesman was substantially heightened by his stint as president on 24. (Let's put it this way: Allstate certainly didn't hire him based on his role, shown here, as crazed Latino slugger Pedro Cerrano ("bats are frightened") in Major League.) But now they've added another, too: actor Dean Winters, who plays bad cop to Haysbert's good cop (good pitchman/bad pitchman?) by explaining all the mayhem that can be avoided if you have an Allstate policy.

Of course, as my buddy Brian Wilson points out on his Personal Injury Blog, there's some mayhem buried in Allstate's policies, too, like its "family member" exclusion: basically, if you're a passenger in a car driven by your teenage son, and he gets into an accident causing you substantial injuries, you're out of luck -- the policy doesn't cover that. I'd thought that all insurance companies had adopted that provision, but no: Nationwide, Grange, Motorists, and Central Mutual don't have it.

I'll have to check with the eyes, the gekko, and Rod Serling to see if GEICO has it.

All we need is Oprah. You know the routine. It's a medical malpractice case, and the plaintiff puts on his experts, several doctors who testify that the defendant's medical practices could only be described as  medieval, and that as a result the plaintiff suffered horrific injuries which will affect him in his every waking moment for the remainder of his life. Then the defense puts on their experts, who testify that the defendant makes Marcus Welby look like the guy on the left, and that not only did the inadvertent severance of the plaintiff's pulmonary artery during surgery not do any damage, but, in a physiological miracle heretofore never observed in the annals of medicine, actually made him better.

medieval, and that as a result the plaintiff suffered horrific injuries which will affect him in his every waking moment for the remainder of his life. Then the defense puts on their experts, who testify that the defendant makes Marcus Welby look like the guy on the left, and that not only did the inadvertent severance of the plaintiff's pulmonary artery during surgery not do any damage, but, in a physiological miracle heretofore never observed in the annals of medicine, actually made him better.

Wouldn't it be fun if all of them got to take the stand at the same time?

Welcome to "concurrent evidence," which also goes under the misleading name "hot-tubbing." Instead of serially presenting the experts, they testify as a group, subject to examination by both sides and the judge and, in some cases, are even allowed to ask each other questions.

The practice originated in Australia, has been authorized by court rule in Canada, and is being implemented on a small scale in the United Kingdom. The results have been mixed. In some cases, especially ones involving numerous experts, there has been a substantial savings of time. Judges seem to like the procedure, because it allows them to see and hear everything at once, rather than try to remember during one expert's testimony what another one said the previous week. And it does take a lot of the partisanship out of the procedure: experts on a panel with others tend to take a more scholarly approach to the questions raised. On the other hand, there are some big procedural hurdles. Opening up a group discussion creates informalities that can easily lead to the introduction of otherwise admissible evidence. And a more aggressive expert can dominate a panel discussion, which may lead an attorney to select an expert with greater emphasis to more charismatic personality traits, rather than expertise or special knowledge. (Like that doesn't happen now anyway.)

Still, don't look for the procedure to be imported into the US anytime soon. The countries mentioned make much greater use of bench trials, especially in complex civil litigation, and the approach works better when the fact-finder does most of the questioning, which isn't really possible in a jury trial. In fact, having judges take over the questioning presents a major problem, even in countries which have adopted it; as one judge commented, "Assuming the judge has an active interest in ferreting out the truth and the experts are candid, I prefer the hot-tubbing option. But those are two bold assumptions, and the procedure drives the attorneys nuts."

Will you take a check? The US national debt is now a bit over $14.25 trillion. Depends on when you read this; as this real-time chart shows, it's increasing even as we speak. That works out to almost $46,000 a citizen, which is a lot of money, even for one so jaded with wealth as myself. Still, it's peanuts compared to what record companies believe Lime Wire owes them. Lime Wire, for the uninitiated, is a program which allows computer users to share files --like, oh, music files -- over the Internet. Back in May, the record companies won summary judgment in a copyright infringement suit, and they just recently filed their request for damages.

And what are those damages? Well, the record companies could try to show actual damages, that because of Lime Wire the record sales for some rock group of limited-talent nobodies was less than it would otherwise have been. Good luck with that. Or it could rely on statutory damages, which Congress has pegged at a maximum of $150,000 per violation.

The record companies alleged that over 9,500 recordings were infringed through Lime Wire, so you just multiply $150,000 by 9,500, and that's the maximum damages, right? That comes to $1.4 billion, which ain't too shabby; if I won a judgment for a client for $1.4 billion, I would probably take the rest of the day off, "rest of the day" in this context meaning "rest of my natural life, and maybe more." But that's  why I drove a Honda Accord to work this morning, instead of being heliported to my office. The attorneys for the record companies argued that they were entitled to $30,000 times the number of times those files were downloaded by individual users, which could number in the millions, resulting in a potential award of $75 trillion.

why I drove a Honda Accord to work this morning, instead of being heliported to my office. The attorneys for the record companies argued that they were entitled to $30,000 times the number of times those files were downloaded by individual users, which could number in the millions, resulting in a potential award of $75 trillion.

Alas, last week, Federal District Judge and former Playboy Bunny-in-training Kimba Wood (no, I am not making that up; Google it, and check out the picture) handed down an opinion rejecting the record companies' theory of damage entitlement, noting that it would be "more money than the entire music recording industry has made since Edison's invention of the phonograph in 1877."

Comments